A friend recently drew my attention to an historical essay about a plan to bring hippos to the U.S. primarily for eating.

Unfortunately, that plan never came to fruition.

Hippos are one of the fatter animals left,

endangered because their meat is so prized,

and I wonder why we don’t just farm them.

In any case, I was curious about eating hippopotamus, and found an interesting section on hippopotamus fat in The Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting: Protein, Fat, or Politics?.

As is evident from some of the previous quotes, the hippo, like the eland, was clearly highly prized for its fat (e.g. Andersson 1857:414; St. Gibbons 1898:9). While hippos may have been too difficult and too dangerous for Paleolithic hunters to kill, it is perhaps not surprising that (presumably) scavenged hippo remains, with clearly cutmarked bones, often show up in some of our earliest archeological sites in East Africa, such as the famous HAS (“Hippo and Artefact”) Site immortalised in a stamp issued jointly in 1975 by Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda (see Fug. 4.4; Isaac and Harris 1997; for additional early cases, see also Bunn 1994; Clark 1987; Fiore et al. 2004; Harmand et al. 2009; Johanson and Wong 2009:255; Leakey 1996:70-71; Plummer et al. 1999;Pobiner et al. 2008).

William Burchell in 1822 provides a concise but useful description of hippo fat, noting its quantity and its somewhat unusually low melting point:The ribs [of the hippo] are covered with a thick layer of fat, celebrated as the greatest delicacy; and known to the colonists as a rarity by the name of `Zeekoe-spek’ (Seacow-pork). This can only be preserved by salting; as, on attempting to dry it in the sun in the same manner as other parts of the animal, it melts away. The rest of the flesh consists entirely of lean; and was, as usual with all other game, cut into large slices, and dried on the bushes; reserving only enough for present use.

Burchell(1822:411)Schweinfurth’s (1978) interesting narrative provides additional insights into the amount of fat that one can obtain from a single hippo carcass; he also comments on the low melting point of the fat, noting additionally that the fat does not go rancid easily:

We were hard at work on the following day in turning the huge carcass of the hippopotamus to account for our domestic use. My people boiled down great flasks of the fat which they took from the layers between the ribs, but what the entire produce of grease would have been I was unable to determine, as hundreds of natives had already cut off and appropriated pieces of the flesh. When it is boiled, hippopotamus fat is very similar to pork-lard, though in the warm climate of Central Africa it never attains a consistency firmer than that of oil. Of all animal fats it appears to be the purest, and at any rate never becomes rancid, and will keep for many years without requiring any special process of clarifying….

Schweinfurth (1878:192)

I then became curious about the composition of hippopotamus fat.

What could make it both have a low melting point and be resistant to rancidity?

Generally, the more saturated a fat is, the more solid it is (that is, the higher a melting point),

but at the same time, the more stable it is — the less it is susceptible to rancidity, because it can’t be easily oxidised.

So how could hippopotamus fat be both very liquid, and very stable?

I eventually found a paper which gives the composition of the fat of a variety of even-toed (cloven-hoofed) animals.

I was perplexed,

because hippo fat appears to be almost the same as beef,

and although it has a little more oleic acid and a little less stearic [*],

which should make it slightly less solid than beef tallow,

it should still be firmer than

lard,

which has even more oleic and less stearic.

Hope temporarily returned when I realised what the point of the paper was, and I learned something new to me.

Fat is usually in the form of a triglyceride.

It’s called that because it consists of three fatty acids held together by a glycerol “backbone”.

The thing I hadn’t read about or thought about before,

is that the properties of triglycerides depend not just on which fatty acids are in them,

but what position they are in the triglyceride.

There appears to be a whole industry built around that.

For example, now that consumers avoid hydrogenated oils,

but still think they should avoid saturated fat,

and still want something spreadable,

engineers have discovered they can make vegetable oils more solid by manipulating the position of fatty acids within triglycerides [†].

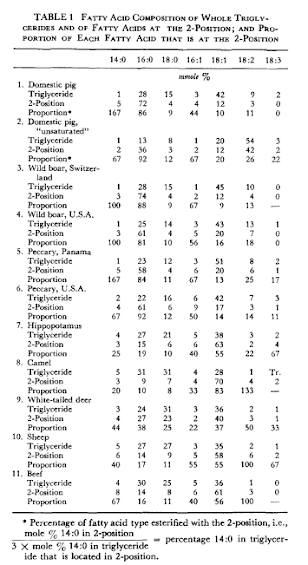

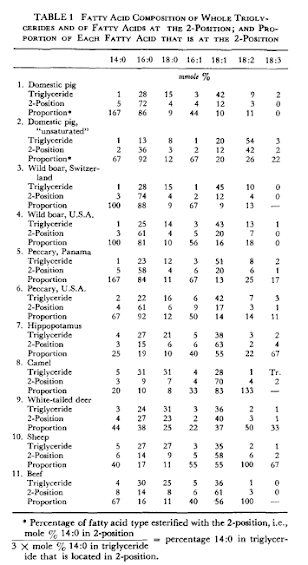

Nonetheless, looking at the table in the paper [‡], not only is the proportion fatty acids in hippo fat similar to beef, so is the distribution of those fats into the middle position of the triglyceride.

So, the mystery isn’t solved that way.

I don’t know what to think.

Another friend pointed out that there are feral hippos in Columbia that no one knows what to do with.

I have an idea…

| [*] | ‘Stearic’ comes from one of the many different Greek words for fat (as important as snow to the Inuit): στεαρ (stear): ‘hard fat’, whereas ‘oleic’ probably comes from ελαιον (elaion): ‘oil’. See The lore of lipids, by Lewis Gidez, in the Journal of Lipid Research 1984 Dec 15;25(13):1430-6 |

| [†] | Here is a fascinating review of the effects of these ‘interesterification’ manipulations:

Tilakavati Karupaiah1 and Kalyana Sundramcorresponding author

Nutr Metab (Lond). 2007; 4: 16.

|

| [‡] | The fatty acid numbers represent chain length and number of double bonds (places where hydrogen could attach), i.e. 0 means saturated, 1 means monounsaturated, and >1 means polyunsaturated. The corresponding names are fatty acid names are:

“The fatty acid distribution in the triglycerides of these various fats is shown in Table 1. For each fat, the first line gives the composition of the whole triglyceride, the second line gives the composition of the fatty acids in the 2-position of the triglyceride, and the third line (Proportion) reports the percentage of each fatty acid that is in the 2-position. If a fatty acid is randomly distributed among all three positions in the triglyceride molecule, the proportion value will be 33%. The occasional proportion value that is in excess of 100% is attributable to the large relative error where a fatty acid is present in very small amounts.”

For more tables of the composition of fats and their second-position fatty acids in a variety plants and animals, see: TRIACYLGLYCEROLS PART 1. STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION |

Oolichan grease might be in this same category? It comes from fish and remains fairly liquid at room tempurature from the photos I have seen that Dr. Jay Wortman has shared in his presentations about The Native Diet of the First Nations people he has studied. Oolichan grease is prepared through a long process of fermenting and cooking and yet it also does not go rancid.

That's an interesting idea, Esmée. It occurred to me when reading your idea, to look into *whale oil*. (Apparently hippos are most closely related to cetaceans.) According to wikipedia, whale oil has a very low viscosity and very high stability. But it also says it is mostly unsaturated, oleic acid.

I am now reading The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living by Phinney & Volek and wanted to share this excerpt regarding Oolican grease…

OOLICAN: THE OLIVE OF THE SEA

But the fat most valued and most extensively traded in aboriginal North America was extracted from an obscure little fish that appeared for just a week along the North Pacific coast every year in March (until recently). From the Klamath River in Northern California to the Aleutians, an icon of the aboriginal people in the region was the oolichan (aka eulachon or candlefish). This little forager of the Pacific came into inlets and estuaries every spring in vast numbers, where for 10 millennia the aboriginal people would gather in anticipation of its return.

The oolichan is up to 20% fat by weight. When you hang it out to dry, it becomes a dry stick that you can light like a candle in your winter lodge so you can see in the dark – thus its name ‘candlefish’. But more importantly, a ton of fresh fish harvested in March yields up to 400 pounds of fat you can extract, store in cedar boxes, and eat throughout the year.

Why process and store oolichan grease? Because not only was it available – it was unique! Unlike the oil from seal, whale, and salmon, oolichan fat is very low in polyunsaturates (both omega-3 and omega-6)[12]. Its primary fatty acids are mono-unsaturated, much like olive oil. That plus its content of saturated fats makes it a semi-solid at ‘room temperature’, so it was much more easily stored and transported in the bent-wood cedar boxes crafted for this purpose by local artisans.

So why might this be? Why wait around for a school of little fish when harpooning a single whale or a few sea lions gives you the same amount of fat? The answer is found in lipid chemistry – the more double bonds you have in a given amount of fat, the sooner it goes rancid. Rancidity occurs when oxygen molecules are added to the fat, changing the taste and destroying its nutritional value. The human nose identifies rancid fat as offensive. And seal, whale, and most fish oils go rancid within a few weeks unless refrigerated or stored in airtight containers, whereas oolichan grease (like olive oil) can be stored for a year or more without going rancid.

In a recent conversation with Bill Moore, a local fisherman of the Niska’a Band in Greenville (Laxgalts’ap), British Columbia, one of us suggested that oolichan grease is like olive oil from the sea. Bill thought for a moment and then responded: “we have been harvesting the oolichan for 9000 years, which is a lot longer than people have grown olives; so maybe we should think of olive oil as oolichan grease from the land.

But there’s another reason why oolichan grease was wildly popular in the pre-contact Pacific Northwest. Again, this can be explained in part by simple chemistry. The human body stores fat for reserve energy to sustain itself if there is nothing else to eat, and our bodies seem to favor the storage of monounsaturates over other classes of fatty acids. Monounsaturates, along with saturates, appear to be what our cells want to burn when they are adapted to burning mostly fat. Oolichan grease is rich in monounsaturates, and thus is more like human fat than anything else in the region. Thus oolichan grease appears to have an ideal fat composition for humans who consume a diet appropriately rich in fat. Somehow, without the benefit of modern chemistry or nutritionists to tell them what to do, a diverse collection of people's inhabiting 3000 miles of the Pacific coastline of North America discovered this, and built their cultures and a regional trade economy around this one source of fat.

~Dr. Stephen Phinney and Dr. Jeff Volek

in The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living

Does not appear for sale online via google search.