This is a copy of an article I wrote for Highbrow Paleo in 2011. I have not edited it.

Several years ago, I had an acquaintance who had previously been diagnosed with diabetes. He began a low carb diet, against the advice of his doctor, (this was in the dark 90′s), and over a period of time his symptoms abated, until one day his doctor announced that he no longer had diabetes (though in a bizarre, but perhaps common feat of cognitive dissonance, she could not help but advise him that he “really should eat more carbs”). Of course, my friend hadn’t actually stopped being a diabetic. If he were to have started eating carbs again, as recommended, he would quickly have returned to his diabetic state. What it means to “be” a diabetic is to have the susceptibility to manifest diabetes under the right, or perhaps I should say wrong, circumstances.

We all have weaknesses, to a greater or lesser extent. We all have our own special ways in which our bodies break down in response to a poor environment. For some diseases, we call this “being”. We “are” diabetic, epileptic, alcoholic, schizophrenic. For some reason, we identify less with other diseases. A person merely “has” cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, or MS, even though these are not considered less permanent conditions once identified, even if they can go into remission. It does seem somewhat arbitrary that a person who was theretofore “normal” suddenly becomes or acquires a disease that they then are or have for the rest of their lives regardless of whether the disease continues to manifest. There may be a sense in which we are all diabetic, for example, even never having had symptoms. We all have the potential to some degree, no matter how small, and just because the degree is not yet known, it doesn’t make it not so.

In any case, what truly matters to a person who is or has or happens to know they have a genetic predisposition to such a condition, is whether or not their body is doing that which characterizes the disease. It is for this reason that one would seek to optimize their environment: to prevent themselves from “doing” a disease state. The Paleo diet and lifestyle is conceived with this in mind. It is reasoned both from an evolutionary standpoint: eat only that kind of food to which the body is well-adapted; and from a clinical perspective: do not eat foods which tend to cause disease. Without seeking to re-enact the environment in which we evolved — an impossible, and not particularly desirable goal (civilization does have some benefits) — one attempts to create a metabolic environment which is maximally healthful, and to which we do not tend to respond by breaking down in our various ways.

For my part, I am a fat person living in a reasonably fit body. (Fat is one of those rare states that we treat linguistically as transient, even though the obese, pre-obese, and post-obese have a signature metabolic profile such that a formerly fat person is not the same as a naturally thin one. This contributes to the blaming of fat people for their condition that would never be tolerated for other diseases.) I have Bipolar II, but for some years now my moods have no longer been disordered, and I use no medication. I wasn’t able to achieve this with a diet that is “just” Paleo, however, or even just low in carbohydrate. My body continues to do fat and bipolar unless I eat nothing but meat (though coffee and tea are mercifully tolerated). No doubt, there are people for whom even this is not enough, and others for whom it is not necessary. My idiosyncratic susceptibilities are simply deeper than most. However, I consider it likely that a great many people will do without disease simply by following a Paleo or low carb diet, or both. If nothing else, they are starting points that make sense for anyone wishing to give their body the best chance to manifest wholeness and well-being, whatever its underlying constitution may be.

Recent changes

I’ve been at this carnivory lifestyle for years now, and I’m still learning how to improve it.

Here are two examples:

- I stopped eating dairy products mid-November.

I already knew I couldn’t eat cottage cheese or yoghurt, without experiencing cravings, but I also gave up hard cheese (which I didn’t eat a lot of, but sometimes at parties), butter, and heavy cream.

I am slowly but surely dropping size.

I’ve been worrying about these last 10 pounds for a couple of years, and now my regular pants are falling down.

Go figure. I mean, Go, Figure!

That’s without extra exercise (the running I talked about in August lasted only a few weeks, and even the weightlifting I usually do was mostly left out over the holidays) and without restricting calories by design.

I interpret this to mean that dairy products were interfering with my satiety, perhaps because of the extra insulin boost they induce.

Unfortunately, I haven’t had serum ketone strips for a while, so I don’t know if this corresponds to higher ketones or not. - I more fully embraced lard.

I set aside the butter, and more recently I also set aside the coconut oil.

(I didn’t use coconut oil when I started carnivory, but I have used it for a long time in the hopes of increasing ketones, and to enjoy in the Bullet-Proof-style coffee.)

I have been known to eat mayonnaise from time to time, just because it tastes good on cold chicken, even though I would otherwise never touch soy or canola oil.

I stopped doing that, too.

You know what I’ve re-discovered?

Bacon drippings.

I’ve been dutifully collecting the stuff for years, filtering it through a paper towel, and frying with it.

Still, it always would get to the point where I had more than I was using.

But now I’m eating it.- With a little salt, I think it is just as good as mayonnaise for egg or chicken salad.

- I blend it into broth, and a cup of that is every bit as delicious as a bullet-proof coffee in my book.

- I still fry with it, but I add more than I used to.

- I dip bites of leaner meat into it.

I’ve shifted my attitude further in the direction of considering fat a food, and in considering plants to be suboptimal sources, even if they happen to have MCTs or high saturated fat content.

Don’t forget that fat is actually an organ. Whoever said that skin was the largest organ in the body was wrong.

Lard doesn’t just have a beautiful fatty acid profile.

It has choline, a little zinc and selenium, vitamin E, and a lot of vitamin D.

Oh yeah, and in stark contrast to butter and coconut oil, it is essentially free. It’s a by-product of something the family already eats, and my rate is still below the supply.

Wait — why eat only meat?

I want to briefly clarify our position about the 30-day trial.

Although we hypothesise that there may be benefits to avoiding or minimising plants,

it is definitely not necessary to avoid plants to gain the benefits of ketosis!

None of the studies that form the basis of our beliefs about ketogenic diets had any such restriction.

As we said in the explanation of the experiment, you can even formulate a vegan diet that is ketogenic.

The 30-day trial can be compared to the original Atkins (1972) induction phase [1] or the Eades’ “meat weeks” in their book The 6-week cure for the Middle-Aged Middle.

While both of those allow a small amount of certain vegetables, one basic idea is shared:

More carbohydrate restriction can be more effective, especially at the beginning, even if you ultimately find a comfortable long-term diet containing more carbohydrate.

In addition to minimising the carbohydrate amount, the main reason we recommend an all-meat diet for the 30-day trial is that it helps avoid these pitfalls:

- Accidentally misunderstanding carb sources (we’ve had several people tell us later they never realised that a food they were eating had that much carb in it).

- More generally, not having to count things, which can be a source of anxiety and error.

- Slippery-sloping: a little leads to a little more until the threshold is passed.

- If you happen to fall on the low side of carb tolerance, you might miss the benefits entirely by choosing the wrong arbitrary cut-off, and then conclude it doesn’t work for you.

- Interference from food intolerances, fiber, or anti-nutrients (such as goitrogens or lectins).

Also, anecdotally, I and several people I have met had profoundly higher benefits from eating just meat. We don’t know the mechanism for sure. Since you are going to all the trouble to try a keto diet anyway, you might as well find out if you are one of those at the same time.

If you are not one of those, you can go back to eating plants and no harm will have been done. I wish you much enjoyment. Vegetables can be exquisite, and I’d cry into my plate about my fate, if I didn’t feel so fantastic and my choices weren’t also excellent.

| [1] | I categorise the Atkins diet into 3 major releases. In the first edition, Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution, there were no products, and there was no notion of “net carbs” (in which you subtract fiber from your carb count). You were allowed up to 2 cups of vegetables from a short list (mostly leafy greens). In the second major release, Dr. Atkins’ New Diet Revolution, this becomes up to 20 grams, which he says is approximately 3 cups of salad, but which can be made up of any foods resulting in that count. The third major release, The New Atkins for a New You, came after his death, and was written by Drs. Westman, Phinney, and Volek. Its induction phase allows 20 grams of net carbs, which ultimately translates into a lot more vegetable matter. There are groups to be found on the internet who live on what they call Atkins 72, because they have found that only that level of restriction works for them. |

Biochemical Warfare

In response to the 30-day trial that Zooko and I recently recommended, one correspondent argued about the importance of plant foods.

He made several points I’d like to address, but the one I want to talk about here is one I’ve heard many times before.

The statement is to the effect that plants are full of a variety of healthful compounds, many of which we have surely not even yet discovered.

This idea has an assumption behind it that I strongly disagree with:

that we evolved to eat a significant amount of plant matter, and therefore we are likely to have optimised our functioning on the biochemical compounds in those plants.

I disagree for the following reasons:

- Whether we evolved eating a lot of plants is contentious.

At the very least, there have been times and places that we had little to none. - What we do know about plants is that their survival strategy is biochemical.

They generate many chemicals (many of which we surely have not even yet discovered) with which to poison their would-be eaters!

My correspondent went on about his diet, listing biochemicals in the foods he eats, and lining them up with diseases those chemicals have been shown to have promise in fighting.

I agree that the biochemicals in plants often turn out to have medicinal properties that we can make use of.

For those properties, the chemical typically has to be extracted to get a high enough concentration to have any effect.

These compounds are much like drugs we make ourselves, in that they usually have unwanted side-effects.

Commonly, they are double edged swords.

For example, some plant chemicals are widely touted because they harm cancer cells.

The bad news is that they also harm your healthy cells.

So like chemotherapy, it is a matter of hoping the healthy cells survive better than the cancerous ones.

In a recent article by Michael Pollan, whose brilliant slogan we bastardised without even a nod (we hope he takes it in stride) [1], he describes how plants produce chemicals, not just as a matter of growing, but in a real-time response to predators.

For example:

“One of the most productive areas of plant research in recent years has been plant signalling. Since the early nineteen-eighties, it has been known that when a plant’s leaves are infected or chewed by insects they emit volatile chemicals that signal other leaves to mount a defense. Sometimes this warning signal contains information about the identity of the insect, gleaned from the taste of its saliva. Depending on the plant and the attacker, the defense might involve altering the leaf’s flavor or texture, or producing toxins or other compounds that render the plant’s flesh less digestible to herbivores. When antelopes browse acacia trees, the leaves produce tannins that make them unappetizing and difficult to digest. When food is scarce and acacias are overbrowsed, it has been reported, the trees produce sufficient amounts of toxin to kill the animals.”

To think that we co-evolved with plants in symbiosis, them providing us with countless, needed medicinal concoctions, while we selectively kill them and eat them, seems a bit naive.

While it’s true that some species rely on having their seeds carried, undigested, for better distribution, or their pollen spread, this is does not imply they get value from having their very bodies eaten.

Even that fruit and nectar need only be helpful to some species;

It didn’t evolve dependent on humans per se.

Finally, I find it a little sad that my correspondent is seeking to avoid disease through constant miniscule doses of medicine that are likely to be accompanied by as much toxin.

There is no evidence that such a strategy has any beneficial effect.

On the other hand, a ketogenic diet has increasingly stronger types of evidence suggesting it will protect against those diseases [2].

As we speak, randomised clinical trials are underway to help clarify whether this is true.

Such is not the case for vegetable eating.

| [1] | For those of you who didn’t recognise it, Michael Pollan famously recommended: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” |

| [2] | See, for example, Zooko’s and my post, The medical-grade diet. |

Deeper ketosis without protein restriction

In my last update, I had talked about the trouble I was having staying at the β-hydroxybutyrate level I wanted while eating to satiety.

Not only was eating to hunger driving my ketone levels down, but higher ketone levels were correlating with irritability.

Hunger and irritability are not my style.

Besides, I have the intuition that something as healthy as ketosis should not entail health compromises.

That’s one reason I think the calorie restricted approach to ketogenic dieting, even in cancer, is likely to be wrong.

More on that another day.

I am delighted to report that for a couple of weeks now I have consistently been in the 1.5 — 3.5 mmol/L range without restricting the quantity of my food, or even trying to be careful about not passing the satiety mark.

Though I do, as always, emphasize fat in my foods, I am not limiting or even measuring my protein intake.

My body’s signals are clear and accurate and I don’t agonize over whether this bite would be the line between enough and too much.

There is no longer any correlation, as far as I’ve noticed, between irritability and higher ketone readings.

The trick seems to be exercise.

A few weeks ago, I made a few lifestyle changes at once.

(I don’t always have time for controls!)

- I started getting up at 5:30 (amended to 5:00 several days later).

- I gave up all but two small cups of coffee a day.

-

I started going to a weightlifting class at the local gym twice a week for an hour.

I enjoy the 15 minute walk home. -

I started running around the block once or twice a day in order to keep up with the 3-year-old riding his strider bike.

That usually involves a little sprinting as we go the downhill direction, and walking or lightly jogging for the rest of the way.

Some days I’ve also done a longer distance walk or bike ride.

There could be some effect of lower carbohydrate contribution from cream, or from something disruptive in the coffee itself.

However, I feel fairly confident that the driving factor is the exercise.

Lyle McDonald: Effects of exercise on ketosis

Way back in 2002, I got my hands on a copy of Lyle McDonald’s The Ketogenic Diet.

It was out of print at the time, and was acquired for me magically by Zooko, in honour of our second anniversary.

(Thank you, Sweetheart!)

Back then, it was one of the few resources available for studying ketogenic physiology.

Lyle McDonald’s purpose in writing his book was to promote Cyclic Ketogenic Dieting for bodybuilding, and dispel myths associated with it.

It is fairly technical, and well-referenced, but it does not presuppose detailed knowledge about specific biochemical pathways, so it’s also accessible.

In it he shows that high intensity exercise (weight training or interval training) is a quick route to establishing ketosis, because it uses up glycogen stores.

In the short term, however, high intensity exercise can decrease ketosis by inhibiting free fatty acid (FFA) release into the bloodstream.

He also emphasizes the utility of low-intensity aerobic exercise, both for lowering glycogen and for increasing FFA for the liver to make ketones with.

Low intensity aerobic exercise is very effective in establishing ketosis, but it takes a long time to deplete glycogen that way.

His bottom line recommendation, then, for establishing ketosis quickly, is to do a high intensity workout to deplete glycogen, followed by 10-15 minutes of low intensity aerobics.

This is precisely what I’ve been doing every day!

Lifting and then walking home, sprinting and then a fast walk around the block, or a long distance, low intensity walk or ride, all qualify as efficient ketosis enhancement.

This is working for me without recourse to hunger-inducing protein restriction.

Fat loss without muscle gain necessarily implies a caloric deficit even though caloric deficit does not necessarily result in fat loss.

Analogously, inducing ketosis through exercise and carbohydrate restriction may well be resulting in a naturally lower protein intake for me.

I don’t really care that much.

I’m eating as much as feels good to me of foods that make me well, and it is no longer interfering with my health goal of being in ketosis.

Whether and to what degree this affects my body composition is not yet clear.

My clothes are fitting better.

I guess I ought to buy a scale.

On lard (from Gary Taubes)

I recently misremembered these figures when talking to friend, so I’m setting the record straight.

“Take lard, for example, which has long been considered the archetypal example of a killer fat. It was lard that bakeries and fast-food restaurants used in large quantities before they were pressured to replace it with the artificial trans fat that nutritionists have now decided might be a cause of heart disease after all. You can find the fat composition of lard easily enough, as you can for most foods, by going to a U.S. Department of Agriculture website called the National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. You’ll find that nearly half the fat in lard (47 percent) is monounsaturated, which is almost universally considered a “good” fat. Monounsaturated fat raises HDL cholesterol and lowers LDL cholesterol (both good things, according to our doctors). Ninety percent of that monounsaturated fat is the same oleic acid that’s in the olive oil so highly touted by champions of the Mediterranean diet. Slightly more than 40 percent of the fat in lard is indeed saturated, but a third of that is the same stearic acid that’s in chocolate and is now also considered a “good fat”, because it will raise our HDL levels but have no effect on LDL (a good thing and a neutral thing). The remaining fat (about 12 percent of the total) is polyunsaturated, which actually lowers LDL cholesterol but has no effect on HDL (also a good thing and a neutral thing).

“In total, more than 70 percent of the fat in lard will improve your cholesterol profile compared with what would happen if you replaced that lard with carbohydrates. The remaining 30 percent will raise LDL cholesterol (bad) but also raise HDL (good). In other words, and hard as this may be to believe, if you replace the carbohydrates in your diet with an equal quantity of lard, it will actually reduce your risk of having a heart attack. It will make you healthier. The same is true for red meat, bacon and eggs, and virtually any other animal product we might choose to eat instead of the carbohydrates that make us fat. (Butter is a slight exception, because only half the fat will definitely improve your cholesterol profile; the other half will raise LDL but also raise HDL.)”

From Gary Taubes in Why We Get Fat: And What to Do About It (emphasis mine).

Update on Ketosis and Weightlifting

Well, that was a really long month. In seriousness, writing frequently is hard for me, not because I’m not constantly brimming with things to say — trust me, I am — but because I have so many other things going on. In, particular, it turns out that raising three children is a lot of work, even when you are well. I also released some software as part of the effort to finish my long-stalled Master’s degree. My hobby site, The Ketogenic Diet for Health, which we started as a way to make progress on writing a book about ketogenic therapies, gets almost no love at all.

So, let me briefly tell you what I learned from actively deepening ketosis, and reintroducing myself to weightlifting.

Deeper Ketosis

I had decided not to measure some things that could be informative, such as protein or calorie intake, and just to focus on eating only when hungry. I started making a lot of fatty broths, and drinking that if I felt what I perceived to be a habitual desire to eat, rather than hunger. I took smaller portions to make my clean-the-plate tendencies less detrimental.

This was effective for increasing blood ketones, and as those went up, I lost weight and fat, at least according to my Tanita scale. I lost about 6 pounds over the course of 2 months. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but I don’t have a lot of weight to lose, and I wasn’t in deep ketosis all the time.

Then I ran out of measuring strips, and soon after that I found my scale in a mysteriously broken state.

Odd things

Here are some particular things I noticed during the process:

- Even though I am already keto-adapted to some degree, I found it hard to stay in the zone I was aiming for (1.5 – 2.5 mmol/L) consistently, because some days eating to hunger meant eating a lot of protein, which drove the ketones down. In other words, staying in deep ketosis for long periods was effortful.

This is strange to me, because theoretically, living off my ample fat stores should allow me to feel satiated indefinitely. As long as I am getting enough protein for body maintenance and blood sugar, why would I ever feel hungry? But I do get hungry, and I do get symptoms like brain fog if I go too long without eating, even when I’ve been in deep ketosis for days.

This brings me to a second point,

- The reason I don’t like to go higher than about 2.5 mmol/L is that I start to get irritable when ketosis gets too high. I figure this must be a blood sugar effect. I haven’t measured blood sugar and ketosis together consistently enough to be sure of a pattern, but other people have reported an inverse relationship, and we found scientific support which we reported here.

Dr. Ede also reported great discomfort in very deep ketosis, although I notice that her blood sugar is not nearly as low as mine gets at similar ketone levels. When my ketosis is above 3mmol/L, my blood sugar gets close to 65mg/dL.

It’s possible that I am simply not sufficiently keto-adapted, but I have suspicions that there is more going on. I’ll get to that in my next post. With any luck that will be sooner than 4 months from now.

Weightlifting

My first idea was to do short sessions every day, rotating parts so that major muscles would get worked a couple of times per week. There were two reasons for this. First, it was very hard for me to get more than 10 minutes of uninterruted time in a day while looking after a 3 year old. Second, sometimes it seems easier to make a habit stick if it is a daily one. Relatedly, missing a day was not devastating.

This worked only okay. I could feel strength gains, but not tremendous ones. I’m not sure why.

Then my schedule changed. Morning preschool sessions started up again after a long winter break, and I found a wonderful person to care for my son on some afternoons, too. I started working out my whole body twice a week, and this seemed to be much more effective. I don’t have a good way of measuring the results. I don’t even have a scale, though scales don’t show recomposition well. Nonetheless, I was feeling stronger, and Zooko seemed to think he could see a difference.

Unfortunately, a couple of weeks ago, as has happened to me many times in the past, a few of life urgencies resulted in missed sessions, and then I lost the habit.

A new scheduling plan

While reading a post by Cal Newport, my favourite productivity blogger, I realized that trying to make every day or even every week the same for the sake of habit building is not necessarily helpful, and in cases like this, it seems harmful.

So my new plan is to take one week at a time. At the beginning of the week I’ll schedule the things I want to get done around all the perpetual idiosyncrasies that make up my life. In other words, instead of planning to work out every Monday and Thursday afternoon, and then falling off the wagon because this week I had to meet the principal on Thursday afternoon, I’m going to be more adaptive.

Ultimately, I need to find ways of operating that promote consistency over a chaotic, ever-changing life situation. I have too much going on to benefit from “bikini bootcamp” style interventions that require me to focus on nothing but getting slim for 10 weeks.

This probably means that it will take me more than 10 weeks to reach my goal, though.

Bottom Lines

Although I could see the beginnings of progress in fat loss from deepening ketosis (which for me amounts to eating less), there were serious sustainability issues that I didn’t anticipate and don’t understand. Some ideas to follow.

Similarly, weightlifting seemed to be having a positive effect, but I need to figure out how to make it happen consistently in the face of constant uncertainty and chaos. This is no different from the struggles I am facing in other arenas of my life, including graduate studies, book writing, and blogging.

The proverbial last 10 pounds

Even though I’m happy with the health effects of my diet, and my weight is stable in a healthy bracket, I still consider myself a little overfat.

Having eliminated most plants from my diet, and given that I believe that weight loss arrived at by enduring hunger is likely to reflect loss of lean mass, not fat,

one might think there was little left for me to try, but that’s not quite true.

There are two obvious changes I could make.

Possibly to the detriment of science, but in the interest of speed and because of the plausibility of synergy, I’ve decided to try both at once.

More Ketosis

The first involves deepening my level of ketosis.

Most of the times that I have measured the level of β-hydroxybutyrate in my blood, it has come out surprisingly low, maybe 0.2 to 0.4.

This is much less than the Phinney-and-Volek-recommended nutritional ketosis range that starts at about 0.5 mMol.

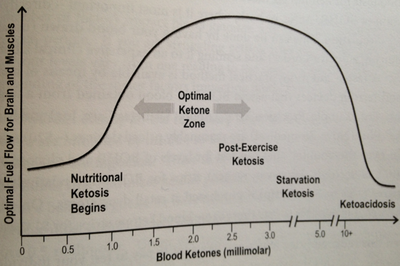

According to them, benefits increase until about 3.0 mMol.

Here is the graphic from their book, which I borrowed without permission from Jimmy Moore.

I hope he doesn’t mind.

I really don’t know what the y-axis means, but it’s clear what their recommendations are.

Given that I eat practically no carbohydrate, this low measurement is probably a reflection of my protein intake.

Although the scientific evidence available on the inverse relationship between protein intake and ketosis in keto dieters is distinctly lacking, it appears to be true anyway.

(I intend to write a post about that on my ketogenic science blog, but don’t hold your breath — it’s complex, and I’m a busy woman.)

I have chosen to leave the evidence of the link between my diet and my blood ketones somewhat unscientific, in that I am not tracking my food.

I have tracked my food extensively in the past, and the problem with it is that the kinds of food I prefer to eat are not easy to analyze, because they aren’t uniform.

For example:

-

One piece of ribeye is fattier than another, especially if at this meal I’m eating the cap and at that meal I’m eating the center.

Moreover, I often buy large, untrimmed pieces and leave the fat on.

My steaks look more like this,than this,

and so I distrust nutritional databases.

- How do I know how much of the bacon grease absorbed into my portion of the scrambled eggs, and if there are also pieces of bacon in it, do I need to take them back out and measure them separately or assume I got an amount proportional to what went in?

- The nutritional composition of homemade broths are anyone’s guess, particularly when there are bits of meat in it.

Because of this complication, when I did that tracking last time, I felt restricted to a subset of foods, and even then the imprecision bothered me.

So I decided not to do it this time.

Nonetheless, I still get to develop my own intuitive sense of what’s going on by taking ketone measurements.

My basic strategy is that when I feel hungry, I take what seem to me small portions of meat, relative to what I had been eating, and eat lots of fat for satiety.

If I start feeling more hunger and fat doesn’t relieve it, I eat a little more meat.

What it lacks in definition, it at least makes up for in simplicity.

I started this on Monday, but the next day I was disappointed to discover that I had carelessly broken my Precision Xtra, and so I couldn’t actually measure blood ketones.

But I found a link to order a free one.

It arrived yesterday, and I am delighted to report that I had a blood ketone measurement of 3.1!

That’s significantly higher than any previous measurement, and I retested later with very similar results, so I don’t think it was an error.

Lifting

The other tack I’m taking is to start lifting weights again.

It’s been maybe a year and a half since the last time I was regularly lifting.

Weight lifting is probably like aerobic exercise, in that by itself it doesn’t lead to fat loss.

For example, take a look at this typical, recent study.

Its abstract points out that the participants who did a combination of aerobic exercise and weight training for 30 minutes, 5 days a week, lost “significantly more” fat than those who did only one of those.

The way the study is written, and the data reported, distract from the fact that these people lost only about 3.3 pounds over 3 months of this intervention.

This is in people who need to lose some 60 pounds of fat to be healthy.

Just imagine yourself 60 pounds fatter than you want to be, committing to 5 days a week of probably commuting to a gym and working out week after week, and coming back 3 months later to find that you have lost 3.3 pounds.

It’s not something I would tout as particularly effective.

Assuming it kept going at that rate (which is unlikely), it would take four and a half years to get to a healthy weight.

Certainly, four and a half years down the road, it would be better to have lost fat at that rate than not to have, but again,

the long-term effects are unlikely to be linear.

The reason for this is that weight composition is a function of your hormonal state, and the effect of the food you eat is by far the dominating factor.

If you combine resistance training with a fat loss diet, though, the effect is to at least preserve lean body mass, and possibly also increase fat loss.

This is true even of non-ketogenic diets.

Unfortunately, there are very few studies that compare ketogenic diets with and without resistance training.

This review reports on two relevant studies.

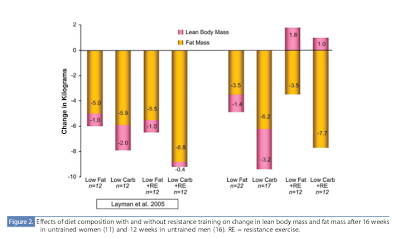

The first compares what it calls low-fat and low-carb diets with or without resistance training.

Even though the “low-carb” diet was nowhere near ketogenically low (38:30:32 percent of carbohydrate to

protein to fat as opposed to 61:18:26 in the low fat group), the results are striking:

In men the difference between either diet alone and that diet + resistance training meant at least as much fat loss but also a gain in lean mass instead of a loss. Women lost lean mass either way, but lost very little in the lower carb + resistance training situation.

In the same paper, Volek reports the results of a similar study he performed in men only.

This time the low carb condition was actually low carb.

(They say

More Vegetable Depletion Studies

This is just a quick follow-up to the last post, Are vegetables good for you?.

In it I mentioned a study, the only one I knew of that actually compared a diet containing almost no fruits and vegetables, to one high in fruits and vegetables containing antioxidants.

It turns out that a subset of those authors went on to follow this with two more studies designed to elucidate this further.

The first, in 2003,

No Effect of 600 Grams Fruit and Vegetables Per Day on Oxidative DNA Damage and Repair in Healthy Nonsmokers

has an apt title.

Here’s the abstract (emphasis mine):

“In several epidemiological studies, high intakes of fruits and vegetables have been associated with a lower incidence of cancer. Theoretically, intake of antioxidants by consumption of fruits and vegetables should protect against reactive oxygen species and decrease the formation of oxidative DNA damage. We set up a parallel 24-day dietary placebo-controlled intervention study in which 43 subjects were randomized into three groups receiving an antioxidant-free basal diet and 600 g of fruits and vegetables, or a supplement containing the corresponding amounts of vitamins and minerals, or placebo. Blood and urine samples were collected before, once a week, and 4 weeks after the intervention period. The level of strand breaks, endonuclease III sites, formamidopyrimidine sites, and sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide was assessed in mononuclear blood cells by the comet assay. Excretion of 7-hydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanine was measured in urine. The expressions of oxoguanine glycosylase 1 and excision repair cross complementing 1 DNA repair genes, determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCR of mRNAs, were investigated in leukocytes. Consumption of fruits and vegetables or vitamins and minerals had no effect on oxidative DNA damage measured in mononuclear cell DNA or urine. Hydrogen peroxide sensitivity, detected by the comet assay, did not differ between the groups. Expression of excision repair cross complementing 1 and oxoguanine glycosylase 1 in leukocytes was not related to the diet consumed. Our results show that after 24 days of complete depletion of fruits and vegetables, or daily ingestion of 600 g of fruit and vegetables, or the corresponding amount of vitamins and minerals, the level of oxidative DNA damage was unchanged. This suggests that the inherent antioxidant defense mechanisms are sufficient to protect circulating mononuclear blood cells from reactive oxygen species.”

In other words, the conclusion is that in healthy people not exposed to high oxidative stress, extra exogenous antioxidants don’t improve things.

Oddly enough, the second, in 2004, The 6-a-day study: effects of fruit and vegetables on markers of oxidative stress and antioxidative defense in healthy nonsmokers has a less decisive title, and reports less decisively negative results, but judging by the description of the subjects and methods, it appears to be a different report on the same study.

I’m not sure what to make of that.

In the discussion they say:

“There is only limited evidence that antioxidants in fruit and vegetables influence oxidative stress or antioxidative defense in healthy subjects. In particular, the contribution of nonnutritive antioxidants to the prevention of oxidative damage is uncertain. The present biomarker-based, fully controlled human intervention study supports the hypothesis that nonnutritive factors, as well as nutritive ones, in fruit and vegetables may influence oxidative damage; however, the effect is not uniformly protective and depends on the molecular structure targeted by each biomarker. ”

It’s not very conclusive.

I’m not going to try to interpret these studies right now, but I wanted to list them for those interested in the topic.

One problem that is interesting to me, though, is that they wanted to keep the macronutrient profiles of the groups the same.

So they gave the non-fruits and vegetables group a drink containing some 60g of simple sugars.

So one could argue that the fruits and vegetables group were at an advantage, because in addition to getting the simple sugars, they were getting factors that mediate sugars, that is, the fiber and possibly the antioxidants.

While fiber is probably not beneficial in and of itself, if you are eating sugars, it can help moderate the damage.

Similarly, if the conclusion from the first study is right, then the times you are going to see an effect of antioxidants, are the times when there is oxidative stress.

Sugar consumption is one such candidate.

So we’ve found ourselves in the situation of comparing apples to sugar.

On the other hand, if they had not done that, then they would be comparing diets either with different caloric intake, or with differing proportions of carbohydrates.

Then if the group not eating so many plants had fared better, it would not have been clear if the effect came from a negative effect of plants, or from the lower calorie / carbohydrate intake.

Although this might appear to be a sloppy design, it’s actually perfectly relevant, because it would address the question of whether or not it is warranted to tell people to replace some of their calories with more fruits and vegetables.

This is a much more realistic question than whether we should tell people to get their carbohydrates from sugar-water as opposed to from fruits and vegetables.

Nonetheless, for some reason, the addition of fruits and vegetables to the diet is heavily advocated, even without such studies in existence.

Are vegetables good for you?

Before I begin, let me briefly talk about my biases.

I would like to emphasize that I always loved eating vegetables.

Even as a child, I enjoyed eating the lowliest, most hated of vegetables, including spinach, broccoli, peas, turnips, and just about everything my talented cooks of vegetarian parents offered me.

Later I discovered, quite by accident, that my most acute health problems could be completely alleviated by going from a very low carbohydrate diet that included large portions of non-starchy vegetables, to an essentially carnivorous one.

However, I mostly have assumed that this drastic health improvement has been in spite of avoiding vegetables.

I have been more likely to hypothesize that this difference is down to extreme carbohydrate intolerance, a need for a particularly deep therapeutic level of ketosis, or that I perhaps have some micro-organism invading my body, such as candida, that will flourish to my detriment even on cabbage, but will leave me alone if I eat only meat.

More recently, and rather reluctantly, I have had to examine whether, in fact, vegetables themselves, or at least some of them, are what is causing me harm.

In this post, I want to point to two sources that have helped me understand and embrace the idea that vegetables not only are not necessary for good health, but they may actually do harm in many people.

The first is a curious small study from 2002 in the British Journal of Nutrition.

The point of the study was to see if the anti-oxidants in green tea have a positive effect on oxidative markers of stress.

In order to make sure the effect was coming from the tea, they removed all fruits and vegetables (except potatoes and carrots) from the subjects’ diets.

The researchers didn’t find any long-term effects from the green tea extract, but they did notice something interesting.

The removal of flavonoid containing elements of the diet did improve those markers.

A “decrease in protein oxidation, in 8-oxo-dG excretion and in the increased resistance of plasma lipoproteins to oxidation in the present study points to a more general relief of oxidative stress after depletion of flavonoid- and ascorbate- rich fruits and vegetables from the diet, contrary to common beliefs.”

In other words, it appeared in this study that not eating fruits and vegetables was better for the participants than eating them.

If nothing else, this must give one pause.

The second I came upon just this week.

At the 2nd Annual Ancestral Health Symposium 2012 (AHS12), Georgia Ede, M.D. gave her presentation titled “Little Shop of Horrors? The Risks and Benefits of Eating Plants”.

In it and on her website, she points out that there are no studies that she could find (and the above is the only one I know of) that actually compares diets with and without vegetables.

The studies that she did find that showed positive benefits to eating vegetables are all flawed in some way such that it can not be determined which aspect of the intervention gave a positive benefit.

For example they had people eat more vegetables and less refined sugar, or eat more vegetables and exercise more.

Moreover, the only studies she found that did not have these confounders, had negative results, that is, they did not show the benefits the researchers were expecting.

Of course, this is only absence of evidence, but with the extensive promotion of vegetables that we are exposed to so vigorously, one would hope to see something more concrete behind it.

Dr. Ede notes that there have been groups in the past that survived fine without vegetables.

She makes cogent arguments against the assertions that fiber is beneficial, and that vegetarians are healthier than non-vegetarians.

She shows that micronutrients are more abundant and/or more bioavailable in animal foods than in plants.

Yet the most important insight she provides from my perspective is that there are many compounds in plants that function as protection for the plant, to prevent it being eaten.

Even though many people can tolerate them at low levels, in high doses (or low doses for sensitive individuals) they are at best double edged swords, and at worst harmful.

This is true even of compounds that have been touted as health-promoting, such as anti-oxidants.

She promises to write about many classes of toxins, and the first article has already been written.

It describes the problems with brassicas (a.k.a. cruciferous vegetables).

When I was on a simply low-carb diet, instead of a “zero-carb” diet (that’s a bit of a misnomer, since there are trace carbs in meat, and I sometimes eat liver or cream, which have a bit more) I ate a lot of those, because they are very low in carbohydrates.

As she claims seems to be the pattern, the ingredients in brassicas that are advertised as fighting disease, also cause problems, actually poisoning mitochondria, generating ROS’s, and more.

I recommend reading her post, and the rest of her site.

I’ll leave with a quote that particularly struck me from the AHS talk:

26:37

“[P]erhaps these compounds are really only irritants that we’ve had to evolve to deal with because we happen to eat them, and maybe [it’s not the case] that they’re actually good for us.”